Introduction

A receptive endometrium and the development of good-quality embryos with potential implantation are required for successful implantation. Despite extensive research endeavors, one of the more enigmatic aspects of assisted reproduction technology (ART) remains the mechanism of embryo implantation. Diverse approaches have been taken in research into embryonic evaluation, encompassing morphological assessments,1 time-lapse studies,2 blastocyst classifications,3 chromosome screening,4 and, recently, the integration of artificial intelligence (AI) into clinical settings as a proposed supplementary tool to enhance embryo selection, thereby increasing the likelihood of successful pregnancies.5,6

In the literature, terminology such as endometrial receptivity,7 window of implantation,8 and blastocyst scores9 is widely encountered. Still, at the time of writing this manuscript, embryo implantation is considered one of the more unknown and obscure topics in assisted reproduction (ART).

Concurrently, various facets to discern optimal conditions conducive to embryonic receptivity have been explored in studies focusing on the endometrium. Valuable insights into understanding endometrial physiology have been provided through traditional approaches, such as ultrasonographic imaging, genetic studies, proteomic diagnosis, biochemical analyses, and electron microscopic evaluations.10–15

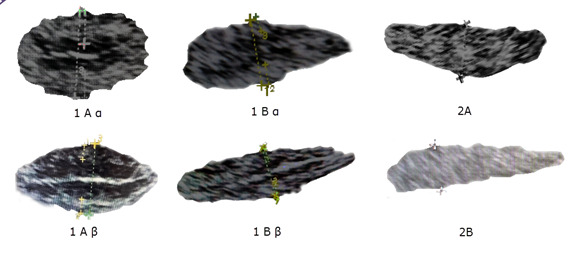

In recent studies, the endometrial pattern and overall thickness have been explored as predictors of embryo implantation and In vitro fertilization (IVF) success. Higher live birth rates with endometrial thickness of 10–12 mm were demonstrated by Mahutte,16 in cycles where a fresh embryo transfer was performed, and in frozen embryo transfer cycles (FET), live birth rates plateaued after 7–10 mm endometrial thickness. The intricate cellular composition of the endometrium has been explored by Greenwald,17 and Yamaguchi,18 surpassing traditional parameters such as trilaminar patterns and overall thickness measurements in their studies. A novel “rhizome” structure, which is an intricate network of endometrial glands extending along the myometrium, has been identified in these studies through the utilization of 3D imaging. This discovery provides a novel framework for comprehending the physiology of the endometrium concerning its receptivity to embryos. Furthermore, a novel endometrial classification system that examines the architectural attributes observed through ultrasound has been recently proposed, providing a new approach to endometrial evaluation and ART success.19

However, although contemporary endometrial evaluation methods have generally improved, the IVF process has remained inefficient. Ideally, methods that enable the selection of both healthy embryos and endometrium will optimize the IVF process and ART efficiency. Notably, AI has been widely used for embryo selection. In our previous study,19 we introduced a methodology that examines both the absolute and relative dimensions of the external layers of the endometrium. This approach departs significantly from conventional, obsolete and misleading paradigms. Our AI model was trained based on the findings related to the external layers of the endometrium. We observed that when the external layers constitute 50% or more of the total endometrial composition in a trilaminar configuration, there is a substantial improvement in pregnancy rates. On the contrary, when the proportion of external layers falls below 50% of the endometrial thickness, a noticeable decline in pregnancy rates occurs. To our knowledge, the applicability of AI in assessing the implantation potential of the endometrium before an embryo transfer has not yet been demonstrated in any study. Our study aims to explore how AI can assist in selecting optimal endometrial development before an embryo transfer. We focus on utilizing ultrasonographic imaging and introduce novel parameters that measure external layers without manual intervention. This innovative approach seeks to identify key factors contributing to successful embryo transfers.

Materials and Methods

Study design and patient population

This retrospective, multicentric study included all infertile patients ≤40 years old, who underwent IVF and a subsequent fresh or frozen embryo transfer from January 2018 through December 2022. The endometrial characteristics in fresh IVF embryo transfer cycles were recorded on the day of HCG trigger, while for FETs, they were recorded before the initiation of progesterone or documentation of luteinizing hormone surge or HCG administration. Only cycles in which blastocysts were transferred were included. Cases of patients harboring chromosomal rearrangements, undergoing preimplantation genetic testing for monogenic defects (PGT-M), having a history of myomectomy, experiencing Asherman syndrome, known thrombophilia or using a gestational carrier were excluded from the analysis. Demographic characteristics such as age, body mass index (BMI), gravidity and ovarian reserve metrics were collected. Cycle characteristics and embryologic data were recorded, including the total number of oocytes retrieved, number of mature oocytes (MII), oocyte maturity rate, fertilization rate, and blastulation rate.

Stimulation protocol

As previously described, patients underwent controlled ovarian hyperstimulation (COH) for IVF.20 Briefly, the COH protocol was selected at the discretion of the Reproductive Endocrinologist. It involved using follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH) and human menopausal gonadotropins (hMG) with a gonadotropin–releasing antagonist and human chorionic gonadotropin. Then patients underwent vaginal oocyte retrieval under sedation 35-36 hours post hCG administration.

Laboratory procedures

Embryo culture

All MII oocytes underwent intracytoplasmic sperm injection, and embryos were cultured to the blastocyst stage.20 Blastocysts were graded upon morphological criteria.21 For the fresh embryo transfer, one or two blastocysts of at least class BB were selected, and the remaining embryos, if viable, were vitrified.

Cryopreservation and rewarming techniques

These techniques have been described previously.20 After embryos were rewarmed, their survival was determined according to the appearance of blastomeres and zona pellucida and the ability of the blastocoel to re-expand. Degenerated embryos were deemed as failed to survive and not used for embryo transfer.

Endometrial evaluation and classification system

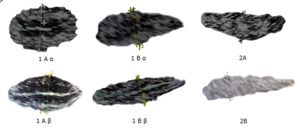

The endometrium was prepared for FET as previously described.19 AI model was trained based on the Asch classification19 using an ultrasonographic endometrial assessment, as follows: 1) well-defined hyperechoic external layers, 2) thickness of the external layers, 3) echogenic midline, 4) entirety thickness of the endometrium, 5) hypoechoic intermediate layer positioned between external layers and midline, and 6) the percentage of external layers relative to the total endometrial thickness (equal or greater than 50%, or less than 50%).19 The resultant classification scheme is summarized in Figure 1: Asch endometrial grading system. Based on the endometrium grading system and the likelihood of pregnancy (previously described), the images were categorized into good and bad.

Outcome measures

The primary outcome was clinical pregnancy rate (CPR), defined as the proportion of patients with fetal cardiac activity detected by ultrasound. Secondary outcomes included negative pregnancy test, defined as a beta HCG level equal or less than 5 mIU/mL, 10 days after embryo transfer.

AI-aided prediction of endometrial receptivity - EndoClassify AI model.

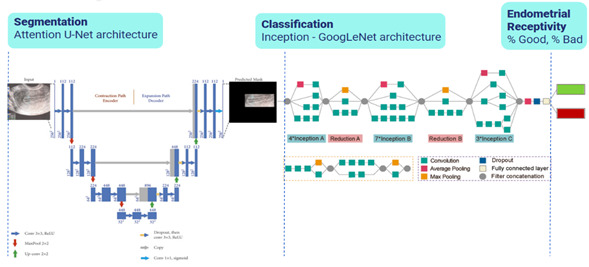

The development of the AI model involved the de-identification of the images selected for the study, image augmentation processes to train the model with high-quality, diverse, and relevant data, followed by the evaluation and selection of segmentation (Attention U-Net) and classification (Inception GoogLeNet) models with a relatively modest computation cost22 (Figure 2: Two-Tiered AI model, segmentation and classification).

A two-tiered AI model (EndoClassify) was implemented using convolutional neural networks. The decision to employ a two-step process was based on the benefits of applying segmentation before classification. Initially, segmentation was applied to isolate regions of interest (ROI) from the endometrial ultrasound images. Subsequently, classifications were applied to assign labels to de-identified ROIs by allowing features to be captured by the network at multiple scales and resolutions. This label indicated the degree of endometrial receptivity, expressed as a percentage of a good or bad endometrium, as defined by our novel endometrial classification system.19

A total of 402 ultrasonographic endometrial images were available for our study, each representing a specific domain with unique features, textures, and anomalies of the endometrium. However, the dataset’s limited size could lead to overfitting and suboptimal performance. To increase the data’s size and diversity and improve the AI model’s accuracy, meticulous image curation was conducted, adding variations and perturbations tailored to each image in the dataset. Throughout this painstaking process, we ensured that the augmented images remained faithful to the domain and encapsulated the intricacies and nuances present in the original dataset.

Additionally, on-the-fly augmentation strategies were implemented directly within the neural network training pipeline. Techniques such as random rotation and flip, feature-wise mean centering, and feature-wise z-score normalization were applied. These strategies offered several advantages, including increased efficiency, reduced storage requirements, and adaptability to changing training scenarios. As a result, this process expanded the collection to include 14.989 images available for training the AI model. Significantly, our model underwent training on a robust dataset comprising 14.989 images, meticulously crafted through diverse augmentation techniques. This extensive dataset originated from an initial set of 331 images, constituting 82% of the total images employed in this study. Additionally, a dedicated validation dataset, consisting of 71 previously unseen endometrial images, was specifically reserved for testing purposes. This subset represents 18% of the total images in our study. It is crucial to note that this validation dataset was employed during the training process to rigorously assess the model’s performance beyond internal metrics. We ensure its reliability and generalizability across diverse populations by testing the model on independent data, incorporating both the training and validation sets. This approach addresses concerns related to overfitting and provides a more comprehensive evaluation of its capabilities in endometrial image classification.

Several metrics were measured using Attention U-Net to determine the segmentation model’s training process. Firstly, an accuracy of 0.88 was achieved by correctly segmenting ultrasound endometrial images. Secondly, a loss score of 0.158 indicated good training performance. Furthermore, the discriminative power in distinguishing between different endometrial conditions was further confirmed by an AUC (Area Under the Receiver Operating Characteristic Curve) score of 0.88.

Various AI classification models were evaluated to assess our final model’s accuracy, precision, and ability to avoid false positive predictions (Table 1). The metrics resulting from the training of other classification models, such as VGG16, ResNet50, and DenseNet, were analyzed, confirming the selection of Inception GoogleNet as the one with better metrics that allowed for the evaluation of the training process and was used to establish the final classification as a good or bad endometrium.

The evaluation process included measuring several key metrics, offering insights into the effectiveness and robustness of the model across different facets of classification. These metrics included Accuracy, Loss, Recall, Precision, AUC, F1 Score, F2 Score, Specificity, and Sensitivity. Each metric offers a unique perspective on the model’s capabilities and highlights its performance under varying conditions.

At the selected classification model inception, an accuracy score of 0.958 indicates a strong ability to classify images into their respective categories correctly. A low loss value of 0.109 signifies that the model converges well during training, minimizing classification errors. The precision value of 0.958 means that the classification model makes accurate positive predictions. The recall value of 0.958 signifies that the classification model correctly identifies most of the relevant instances within the dataset.

An AUC value of 0.992, which is very close to 1.0, reflects the model’s outstanding performance. The F1 Score value of 0.927 indicates a strong balance between precision and recall in the classification model, making it effective at correctly classifying positive instances while minimizing false positives and false negatives. The F2 Score value, such as 0.928, indicates that recall is prioritized more than precision by the classification model, which is especially useful when minimizing false negatives is more critical than minimizing false positives.

A specificity value of 0.931 indicates that negative instances are effectively identified by the classification model, avoiding false positive predictions. A sensitivity value of 0.931 indicates that positive instances are effectively identified by the classification model, minimizing false negatives. Collectively, these metrics demonstrate the effectiveness and reliability of the model in classifying endometrial images.

Results

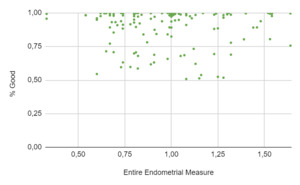

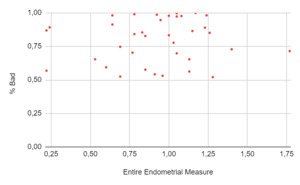

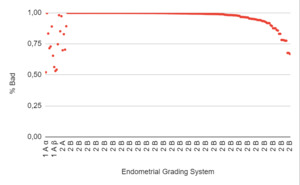

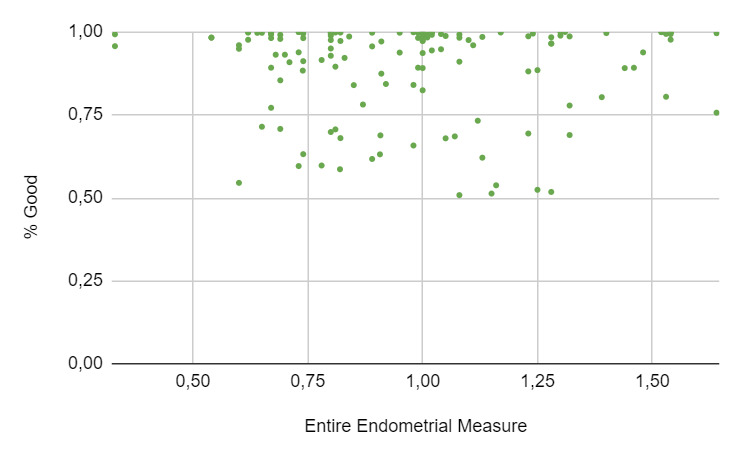

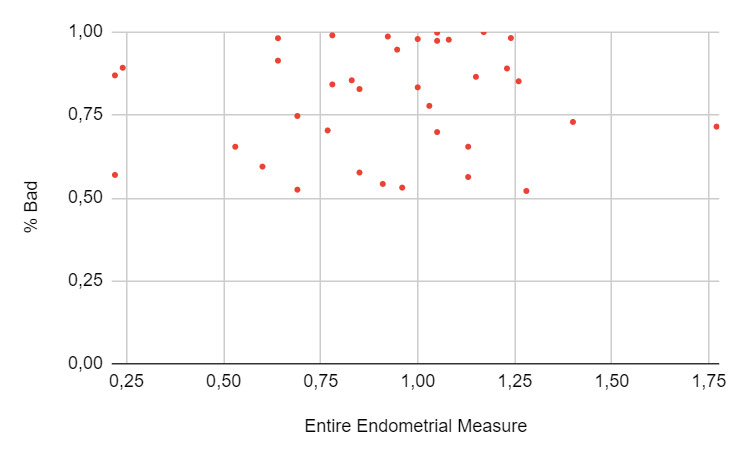

A total of 271 women underwent an embryo transfer during the study period. No differences were found in age, BMI, ovarian reserve metrics and cycle characteristics among cohorts. A total of 402 ultrasonographic endometrial images were available for analysis. When the results of the EndoClassify AI model were analyzed, it was observed that 86.5% of the images with an entire endometrial measurement greater than or equal to 7mm were assigned to the “good” category (Figure 3: % Good endometrium identified by AI vs Entire Endometrial Measure). Conversely, it was observed that 25% of the images with an endometrial measurement of less than 7mm were assigned to the “bad endometrium” category (Figure 4: % Bad endometrium identified by AI vs Entire Endometrial Measure).

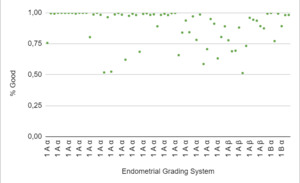

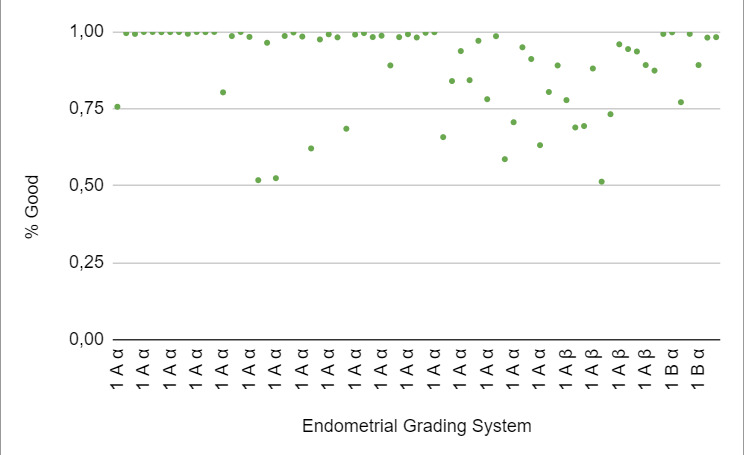

When stratified according to the Asch endometrial grading system,19 category 1Aα corresponded to 71% of the “good” endometrium, and this category had a CPR of 74%. Category 1Aβ corresponded to 19%, and a CPR of 15% was observed in this category. The remaining 10% corresponded to category 1Bα, and a CPR of 11% was observed in this category (Figure 5: % Good endometrium identified by AI vs Endometrial Grading System).

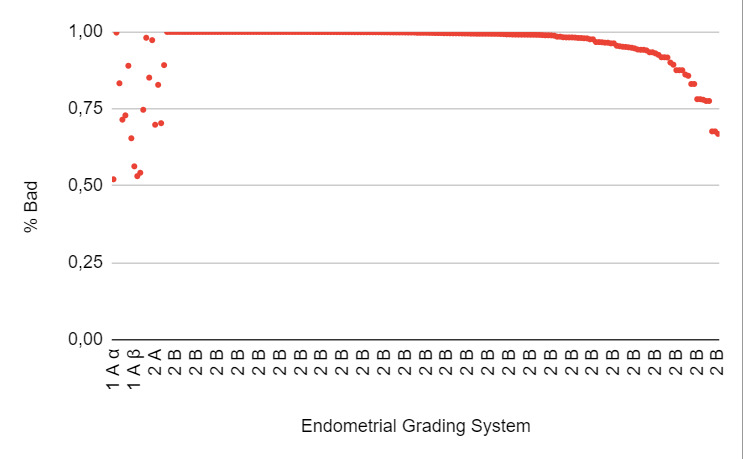

When the “bad endometrium” identified by the AI model was analyzed, it was observed that 1.5% corresponded to category 1Aα, and 2% had a negative pregnancy test result. Additionally, 3.4% corresponded to category 1Aβ, with 90% having a negative pregnancy test result. 1% corresponded to category 1Bα, with 8% having a negative pregnancy test result. Furthermore, 2.5% corresponded to category 2A, and 91.7% corresponded to category 2B, with both endometrial categories considered unsuitable for embryo transfer (Figure 6: % Bad endometrium identified by AI vs Endometrial Grading System).

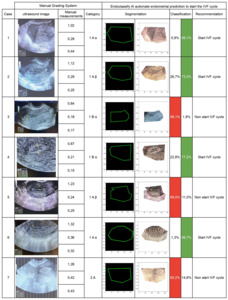

To further demonstrate the benefits of using the novel categorization system and how the EndoClassify AI model goes beyond manual categorization by sorting into the ‘Bad’ or ‘Good’ categories and predicting CPR, an analysis of 7 cases (Table 2) was provided. Cases 1, 2, 4, and 6 were classified as “good endometrium” and were recommended to proceed with the embryo transfer cycle. In contrast, cases 3, 5, and 7 were classified as “bad endometrium” and were recommended for the cancellation of the cycle.

Discussion

The results of this analysis suggest that the endometrial implantation potential may be predicted using AI. While AI applications in evaluating information about oocytes and embryos have been explored in numerous studies,5,11,21–23 there are currently no effective diagnostic tools to predict pregnancy outcomes by evaluating the endometrium.24 Our study is the first to use AI to evaluate the endometrium in women undergoing ART.

The introduction of the EndoClassify AI model enhances the assessment of the endometrium by introducing a new method to evaluate endometrial conditions based on transvaginal ultrasound images. Image quality is objectively evaluated by this model, and images are categorized as either ‘Good’ or ‘Bad’ according to a rigorous set of criteria. Furthermore, valuable insights are provided by quantifying the percentage likelihood of pregnancy for each classification, furnishing clinicians with essential information for decision-making regarding embryo transfer or the postponement of the cycle.

AI offers advantages upon integration, such as reduced error rates and engagement in logical machine reasoning devoid of emotional factors or physical constraints. However, challenges in AI adoption encompass substantial initial deployment costs, ethical considerations surrounding the reliance on machines to replace human decision-making, and the absence of a human connection. It is crucial to underscore that no supercomputer should supplant or substitute for human decision-making. Addressing these intricate challenges will necessitate meticulous thought and reflection.

Our study is the first to use the novel classification with an AI model to assess the endometrium before an embryo transfer. Patients with recognizable risk factors for implantation failure, such as parental chromosomal rearrangements, uterine factor infertility, and known thrombophilias, were excluded from the analysis, thus making our findings more generalizable.

Notwithstanding our best efforts to avoid biases, some shortcomings and limitations exist in the analysis. The most notable limitation is its retrospective design, which increases the chance of selection bias. In addition, both fresh and frozen embryo transfers were included in the study. Furthermore, we focused on imaging evaluation to create our AI model, and important confounders such as embryo ploidy and infertility diagnosis were not accounted for. Nevertheless, the belief is held that our AI model will usher in a digital transformation and automation in the realm of reproductive medicine, ultimately offering significant advantages to infertile patients. AI is envisioned as a valuable tool to support medical practitioners, elevating diagnostic capabilities and improving treatment efficiency. The role of AI is seen as a complement to reproductive medicine practitioners and embryologists, aiming to streamline their efforts and better assist patients rather than replace them. It is tempting to speculate that utilizing a combination of AI on embryos and endometrium in the same patient, we could achieve very high success rates in IVF.

Conclusion

Our report underscores the transformative potential of the EndoClassify AI model, showcasing a strong correlation with clinical research outcomes in the domain of ART practices. The findings lead to an optimistic conclusion, envisioning a future where AI and clinical expertise seamlessly collaborate, contributing to improved healthcare outcomes in the field of ART.

Declaration of generative AI and AI-assisted technologies in the writing process

During the preparation of this work, the authors used Chat GPT to improve calligraphy and English. After using this tool, the content was reviewed and edited as needed, and the authors assumed full responsibility for the publication’s content.

Authors’ Contribution per CRediT

Conceptualization: Ricardo H Asch Schuff (Equal), Jorge Suarez (Equal). Data curation: Ricardo H Asch Schuff (Equal), Jorge Suarez (Equal). Formal Analysis: Ricardo H Asch Schuff (Equal), Jorge Suarez (Equal), Nicolas Laugas (Equal). Investigation: Ricardo H Asch Schuff (Equal), Jorge Suarez (Equal). Methodology: Ricardo H Asch Schuff (Equal), Jorge Suarez (Equal), Nicolas Laugas (Equal). Project administration: Ricardo H Asch Schuff (Lead). Software: Ricardo H Asch Schuff (Equal), Jorge Suarez (Equal), Nicolas Laugas (Equal). Supervision: Ricardo H Asch Schuff (Equal), Jorge Suarez (Equal), Tamar Alkon (Equal). Validation: Ricardo H Asch Schuff (Equal), Jorge Suarez (Equal), Nicolas Laugas (Equal). Visualization: Ricardo H Asch Schuff (Equal), Jorge Suarez (Equal), Nicolas Laugas (Equal). Writing – original draft: Ricardo H Asch Schuff (Equal), Jorge Suarez (Equal), Marlene L. Zamora Ramirez (Equal), Tamar Alkon (Equal). Writing – review & editing: Ricardo H Asch Schuff (Equal), Jorge Suarez (Equal), Marlene L. Zamora Ramirez (Equal), Tamar Alkon (Equal).