Introduction

Infertility is a common condition that has continued to affect human race since medieval ages. Even in modern times it has continued to be a source of concern to many families as the need for procreation and preservation of family lineage has remained an invaluable attribute of many cultures.1 Worldwide, infertility is generally believed to have several impacts on society ranging from social, cultural, economic, medical, demographic and psychological effects. Undoubtedly, it has remained a very sensitive issue in Africa where large family size is equated with family wealth and inheritance, just as involuntary childlessness has been fingered as focal cause of lack of harmony in many homes.2–4

Couples’ desire for fertility care has grown substantially in recent years in Nigeria.5,6 This may be attributed to many factors such as the increase in the number of fertility care centres, improved success rate of fertility treatment, increased awareness of treatable causes of infertility and incorporation of fertility centers in many government-owned health care facilities across the country.6,7 Conventionally, the infertility burden worldwide has been relatively stable. It is generally estimated that about 1 in 6 couples will have difficulty conceiving. Along those lines, it is believed that about 84% of couples will achieve pregnancy after one year of regular, unprotected, peno-vaginal intercourse.7,8Therefore, the inability to achieve or sustain pregnancy after this period may be attributed to the couples’ previous or current chronic medical conditions, sexual, previous reproductive history, age, physical examination findings, availability of diagnostic testing, or any combination of those factors.7,8

Just as important, causes of infertility, has long been classified as male, female, combination of both and unexplained infertility. Female causes can be attributed to Ovulatory dysfunction, tubal damage, uterine problems (fibroids, polyps, synechia, adenomyosis), endometriosis, coital and cervical causes while male factor could be due to pre-, testicular, and post-testicular causes. The pattern of infertility defers according to region and cohort of women studied.9–12 However, it is believed that tubal factor infertility is common in Africa due to poorly treated pelvic infections.7,13–20

The primary objectives of this research are threefold: first, to quantify the prevalence of BBVs within the target population; secondly, to analyze the associations between specific risk factors and the presence of these viruses; and third, to evaluate the potential impact of targeted interventions based on the findings. We hypothesize that poor educational attainment and extremes of maternal age may demonstrate a higher prevalence of BBVs compared to the general population. Furthermore, we expect to identify particular risk factors, such as age, poor education, unemployment status, that may significantly contribute to increased rates of infection. Ultimately, this study seeks to provide valuable insights for public health initiatives aimed at reducing the transmission of BBVs and improving health outcomes for vulnerable populations in Nigeria.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Study Design and Setting

This study employed a retrospective cohort design to investigate couples seeking fertility care at the Assisted Conception Unit of the Lagos University Teaching Hospital. The study period spanned from January 1, 2015, to December 31, 2023.

Study Population

The participants included couples who presented for fertility evaluation and treatment during the specified timeframe.

Eligibility Criteria

Inclusion Criteria

Couples in which both partners had difficulty conceiving after one year of regular, unprotected coital attempts, and who sought care or received treatment at our facility during the study period.

Exclusion Criteria

Couples with incomplete medical records or those who had been trying to conceive for less than one year prior to seeking assistance.

Data Collection

An anonymized Excel spreadsheet was utilized to systematically collect relevant demographic and clinical information from the couples. This included data on ages, body mass index (BMI), and infertility factors.

Data Analysis

The collected data were entered into the Excel spreadsheet, which was subsequently imported into SPSS Statistics version 29.0 for analysis. Descriptive statistics (mean and standard deviation for continuous variables, and frequencies and percentages for categorical variables) were calculated. Statistical analyses included chi-square tests to assess associations between categorical variables and regression analyses to evaluate the effects of maternal age, BMI, paternal age, and BMI on the duration of infertility and sperm parameters. Statistical significance was determined at a p-value of less than 0.05.

Infertility Assessment

Ovulation was assessed using mid-luteal phase progesterone levels. Tubal patency was evaluated through Hysterosalpingography (HSG), while uterine factors were assessed via transvaginal ultrasound. Male infertility was evaluated by performing seminal fluid analysis in accordance with the WHO 2021 guidelines. Testing for blood borne viruses, including Hepatitis B and C and HIV, was conducted as part of the final evaluation before assisted conception.

Ethical Considerations

Ethical approval for the study was obtained from the hospital’s ethical review board, and all patient data were anonymized to maintain confidentiality throughout the research process.

Results

A total of 236 couples underwent evaluation at the Assisted Conception Unit during the study period. The demographic characteristics of the participants revealed that the mean age of females was 40.89 ± 6.8 years, while males had a mean age of 43.40 ± 4.4 years. The primary infertility duration among couples ranged from 1 to 12 years, with an average of 5.5 years- Table 1.

Infertility Patterns

The analysis of infertility factors indicated that combined male and female factor infertility was present in 33.9% of the cases. Female factor infertility had a prevalence of 41.9%, with the leading contributors being Ovulatory disorders (25.3%), followed by tubal factors (59.7%). Notably, right-sided tubal blockages were recorded more frequently than left-sided blockages-Table 2.

Socio-Demographic Factors and Infertility Outcomes

The analysis of socio-demographic factors revealed notable trends that may influence infertility outcomes. Educational status was assessed as a potential determinant of infertility patterns. Among the participants, 67.8% had tertiary education, while 32.2% had secondary education. Couples where the female partner had tertiary education exhibited a slightly lower prevalence of unexplained infertility (7.5%) compared to those with secondary education (12.5%), suggesting that higher educational attainment may contribute to greater awareness and earlier intervention in addressing infertility. Further, residence location (urban, semi-urban, rural) was examined for its correlation with the duration of infertility. Rural-dwelling couples were more likely to present with longer infertility durations (≥10 years, 23.4%) compared to their urban counterparts (37.1%). This may reflect disparities in access to fertility care and awareness between urban and rural populations. These findings highlight the importance of considering socio-demographic factors such as education and residence when tailoring infertility interventions. Future studies should explore these relationships in greater detail to inform targeted public health strategies- Table 1.

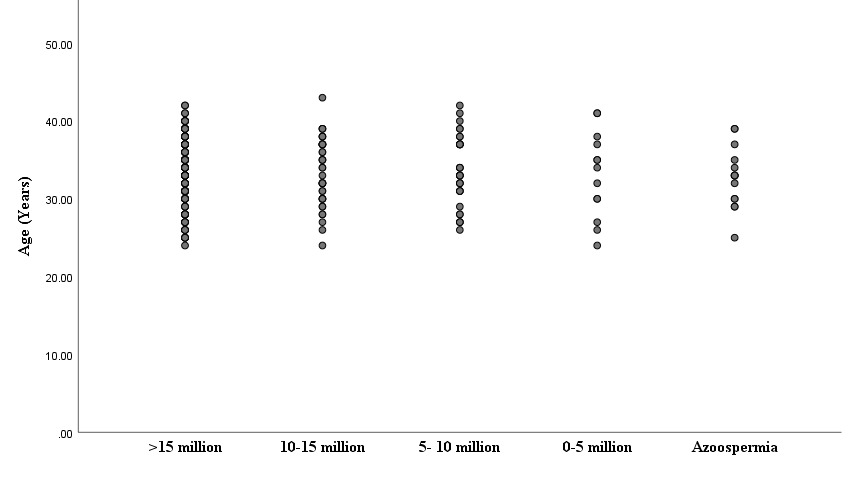

Semen Analysis

Among the males in the study, semen analysis revealed abnormal sperm parameters in 60.1% of cases. A significant inverse relationship was found between paternal BMI and sperm concentration, showing that higher paternal BMI corresponds to lower semen density, with a statistically significant p-value of <0.01. Figure 1.

Prevalence of Bloodborne Viruses

Testing for blood borne viruses revealed that 8.9% of participants were positive for Hepatitis B, while 4.7% tested positive for HIV. The presence of these viruses was notably higher among females compared to males, indicating a potential concern for maternal health in assisted reproductive technologies. The prevalence of bloodborne viruses (BBVs) observed in this study, including Hepatitis B (8.9%) and HIV (4.7%), highlights the need for integrating specific measures into fertility treatment protocols. Routine BBV screening for couples undergoing assisted reproductive technologies (ART) is essential to identify and manage infections effectively. This ensures the safety of both patients and medical personnel while minimizing the risks of vertical and horizontal transmission during ART procedures. For patients with Hepatitis B, pre-treatment with antiviral therapy and careful monitoring during ART cycles can significantly reduce the risk of maternal-fetal transmission. Similarly, HIV-positive individuals can benefit from sperm washing techniques and adherence to antiretroviral therapy to enhance the safety and success of conception efforts. Implementing infection control measures, such as dedicated equipment, separate laboratory protocols, and enhanced sterilization practices, is crucial for reducing the risk of cross-contamination within fertility clinics-Table 3 and 5.

Statistical Analysis

Regression analyses demonstrated that increasing maternal age was significantly associated with a longer duration of infertility (p < 0.05) and a decrease in sperm parameters. Further analysis showed no statistically significant correlation between maternal BMI and fertility outcomes, suggesting that paternal factors might play a more critical role in the success of assisted reproductive interventions.

The findings emphasize the multifactorial nature of infertility in this cohort, highlighting the need for comprehensive evaluations that consider both partners’ health to tailor appropriate treatment strategies Table 4.

Discussion

Comparative Analysis of Infertility Patterns

The predominance of secondary infertility observed in this study aligns with patterns reported in sub-Saharan Africa, where infections, post-abortal complications, and poorly treated pelvic inflammatory disease are significant contributing factors. However, regional variations within Nigeria remain underexplored. For instance, studies from northern Nigeria, such as those by Panti and Sununu, have highlighted a higher prevalence of primary infertility, suggesting potential differences in socio-cultural factors, healthcare access, and infection rates between geopolitical zones.14,19,21–25

Internationally, the study’s findings on BBV prevalence differ from patterns observed in high-resource settings. For example, Canadian studies have reported significantly higher prevalence rates of BBVs among fertility patients, likely due to differing healthcare systems, population demographics, and screening practices. In contrast, the relatively lower prevalence of BBVs in this study might reflect differences in access to diagnostic testing or public health initiatives in Nigeria.26–30

The high proportion of tubal factor infertility in Lagos, attributed to untreated infections, resonates with findings from East African studies but contrasts with trends in developed countries, where advanced maternal age and lifestyle factors often dominate. Similarly, the observed impact of paternal obesity on semen parameters is consistent with global research but underscores the need for targeted interventions tailored to the local population.8,13–15

To deepen our understanding of these patterns, future studies should incorporate multi-regional and cross-country comparisons, exploring the interplay between socio-economic, cultural, and healthcare factors. Such research could inform region-specific strategies to improve fertility outcomes and address disparities in infertility care.

Implications of Male Infertility and the Impact of Obesity on Reproductive Health

The findings of this study underscore the significant role of male infertility, particularly the adverse effects of obesity on reproductive health. The observed inverse relationship between paternal BMI and semen concentration highlights the critical impact of male health on fertility outcomes. This aligns with global evidence suggesting that obesity negatively affects sperm quality, including parameters such as concentration, motility, and morphology.20–24

Obesity contributes to reproductive dysfunction through several mechanisms, including hormonal imbalances caused by increased aromatization of testosterone to estrogen in adipose tissue. This hormonal shift disrupts the hypothalamic-pituitary-gonadal axis, impairing spermatogenesis. Furthermore, obesity-related conditions, such as insulin resistance, chronic inflammation, and oxidative stress, can lead to DNA damage in sperm, reducing fertility potential.24–26

The implications for fertility treatment are profound. Addressing paternal obesity should be a priority in preconception care, as lifestyle modifications, including weight loss, improved diet, and increased physical activity, have been shown to enhance sperm parameters and overall reproductive outcomes. Fertility clinics should integrate counseling and support for men regarding the importance of achieving a healthy BMI as part of a comprehensive approach to infertility management.

In addition, the findings highlight the need for routine assessments of male partners during infertility evaluations. Historically, male infertility has often been overlooked, but these results emphasize its critical contribution to overall reproductive health. Future research should explore the broader effects of male obesity on ART outcomes, including fertilization rates, embryo quality, and live birth rates, to develop targeted interventions that optimize treatment.7,27,28

Non-Significant Results and Their Potential Implications

While this study identified several significant relationships, such as the inverse correlation between paternal BMI and semen concentration, some variables did not demonstrate statistically significant associations. For instance, the analysis showed no significant correlation between maternal BMI and infertility outcomes, which contrasts with findings from other studies that have reported maternal obesity as a factor influencing ovulatory dysfunction and pregnancy rates. This lack of significance could be attributed to the sample size, population-specific factors, or differences in lifestyle and genetic predispositions within the studied cohort.30–32

Similarly, no statistically significant association was found between male age and semen quality parameters (Figure 2). This result diverges from global research that suggests advancing male age negatively impacts sperm DNA integrity and fertility outcomes. These findings may reflect regional variations or indicate that other factors, such as BMI and lifestyle, play a more prominent role in this population.33,34

The absence of significant correlations in these areas suggests that additional research is needed to explore potential confounding variables, such as dietary habits, physical activity levels, or environmental exposures, which may influence these relationships. Furthermore, these findings emphasize the importance of individualized approaches to infertility management, as the impact of certain factors may vary across populations.

Implications of BBV Prevalence on Fertility Treatments

The prevalence of bloodborne viruses (BBVs), including Hepatitis B (8.9%) and HIV (4.7%), among couples seeking fertility treatments in this study underscores critical considerations for assisted reproductive technologies (ART). These findings highlight the importance of routine BBV screening as a standard component of infertility evaluations. Early identification of BBV-positive patients enables timely medical interventions, improving patient outcomes and reducing the risk of viral transmission.35

In fertility treatment protocols, managing BBVs involves multiple layers of intervention. For instance, individuals with Hepatitis B may require prophylactic antiviral therapy prior to undergoing ART to minimize maternal-fetal transmission risks.36 Similarly, HIV-positive patients can benefit from sperm washing techniques, which help reduce the potential for viral transmission during conception. Antiretroviral therapy must also be optimized for both partners to ensure safety and efficacy during the treatment process.

Furthermore, the presence of BBVs necessitates robust infection control measures in fertility clinics. This includes using dedicated laboratory equipment, implementing separate protocols for handling samples, and ensuring rigorous sterilization processes to prevent cross-contamination. These protocols are vital not only for safeguarding BBV-positive patients but also for protecting BBV-negative individuals and healthcare staff involved in ART procedures.37

The observed prevalence of BBVs in this study serves as a reminder of the need for comprehensive guidelines in fertility clinics, especially in regions with a higher burden of infectious diseases. Incorporating routine screening and tailored interventions into ART protocols will enhance treatment safety and efficacy while addressing public health concerns related to BBVs in reproductive healthcare. Future research should explore the cost-effectiveness and clinical outcomes of integrating these measures into standard fertility care practices.

Conclusion

This study provides important insights into the prevalence and patterns of infertility among couples seeking assisted conception in Lagos, Southwest Nigeria, highlighting several key factors that influence reproductive health outcomes. The findings emphasize the need for a comprehensive, evidence-based approach to infertility management that addresses both clinical and public health challenges.

Prevalence and Patterns of Infertility

The study revealed a significant burden of secondary infertility, with female factor infertility being slightly more prevalent than male factor infertility. Tubal pathology emerged as the most common contributor to female infertility, reflecting the impact of untreated pelvic infections and the need for enhanced reproductive health services. In men, abnormal sperm parameters were observed in a majority of cases, with combined male and female factor infertility accounting for a considerable proportion of cases. These trends underscore the multifactorial nature of infertility, necessitating comprehensive assessments of both partners during infertility evaluations.

Impact of Male Obesity on Fertility

The inverse relationship between paternal BMI and semen concentration highlights the critical role of male health in reproductive outcomes. Obesity in men disrupts spermatogenesis through hormonal imbalances, oxidative stress, and chronic inflammation, ultimately impairing sperm quality. These findings align with global evidence and emphasize the importance of addressing lifestyle factors, such as obesity, to improve fertility outcomes. Lifestyle interventions targeting weight management should be integrated into preconception care for men to optimize reproductive health.

Prevalence and Implications of Bloodborne Viruses (BBVs)

The study identified a relatively low prevalence of bloodborne viruses (BBVs), including Hepatitis B (8.9%) and HIV (4.7%), among the study population. However, these infections present significant risks in the context of assisted reproductive technologies (ART). Routine BBV screening should be a standard practice in fertility care to facilitate early detection, tailored interventions, and infection control measures, ensuring safe and effective treatment for all patients.

Regional and Contextual Variations

The variability in infertility patterns observed across different regions highlights the influence of socio-cultural and healthcare factors on reproductive health. This calls for further research to explore these variations in greater depth, particularly in underrepresented regions, to inform policies and practices tailored to specific populations.

Future Directions and Public Health Recommendations

Targeted public health interventions are essential to address the dual challenges of male obesity and BBV prevalence in infertility care. Campaigns promoting healthy lifestyles among men of reproductive age and integrating routine BBV screening into fertility care protocols are critical for improving reproductive outcomes and protecting the health of patients and offspring. Multicenter studies and collaborations should further investigate these factors to refine treatment strategies and enhance the quality of infertility care.

Final Statement

A holistic, patient-centered approach to infertility management—incorporating thorough health assessments, lifestyle modifications, and infection screening—is key to addressing the complex challenges of infertility. These findings serve as a foundation for improving reproductive healthcare and ensuring equitable, effective treatments for couples facing infertility in diverse settings.

Strength and Limitations

This study addresses a critical issue of infertility in a specific Nigerian context, making it relevant and timely. It also has a relatively large sample size, enhancing the reliability of the results and provides a comprehensive analysis of both infertility patterns and blood borne virus prevalence. However, there is a lack of detailed qualitative data to supplement the quantitative findings. In addition, the retrospective design of this study limits causal interpretations, so also is the non-inclusion of certain laparoscopic findings which invariably restricts a thorough evaluation of tubal pathology.

Disclaimer (Artificial Intelligence)

We hereby declare that no generative AI technologies such as Large Language Models (ChatGPT, COPILOT, etc.) and text-to-image generators have been used during writing or editing of this manuscript.

Author Contribution per CRediT taxonomy

Conceptualization: Sunday I. Omisakin (Equal), Aloy O. Ugwu (Equal), Olaniyi A. Kusamotu (Equal), Adebayo Awoniyi (Equal), Olajide A. Fagbolagun (Equal), Christian C. Makwe (Equal), Joseph A. Olamijulo (Equal), Ayodeji A. Oluwole (Equal), K.S. Okunade (Equal). Data curation: Sunday I. Omisakin (Equal), Aloy O. Ugwu (Equal), Olaniyi A. Kusamotu (Equal), Sunusi R. Garba (Equal), Adebayo Awoniyi (Equal), Olajide A. Fagbolagun (Equal), Christian C. Makwe (Equal), Joseph A. Olamijulo (Equal), Ayodeji A. Oluwole (Equal), K.S. Okunade (Equal), O.K. Ogedengbe (Equal), O.F. Giwa-Osagie (Equal). Formal Analysis: Sunday I. Omisakin, Aloy O. Ugwu (Equal), Olaniyi A. Kusamotu (Equal), Olajide A. Fagbolagun (Equal), Christian C. Makwe (Equal), Joseph A. Olamijulo (Equal), Ayodeji A. Oluwole (Equal), K.S. Okunade (Equal). Investigation: Sunday I. Omisakin (Equal), Aloy O. Ugwu (Equal), Olaniyi A. Kusamotu (Equal), Sunusi R. Garba (Equal), Adebayo Awoniyi (Equal), Olajide A. Fagbolagun (Equal), Christian C. Makwe (Equal), Joseph A. Olamijulo (Equal), Ayodeji A. Oluwole (Equal), K.S. Okunade (Equal), O.K. Ogedengbe (Equal), O.F. Giwa-Osagie (Equal). Methodology: Sunday I. Omisakin (Equal), Aloy O. Ugwu (Equal), Olaniyi A. Kusamotu (Equal), Sunusi R. Garba (Equal), Adebayo Awoniyi (Equal), Olajide A. Fagbolagun (Equal), Christian C. Makwe (Equal), Joseph A. Olamijulo (Equal), Ayodeji A. Oluwole (Equal), K.S. Okunade (Equal), O.K. Ogedengbe (Equal), O.F. Giwa-Osagie (Equal). Resources: Sunday I. Omisakin (Equal), Aloy O. Ugwu (Equal), Olaniyi A. Kusamotu (Equal), Sunusi R. Garba (Equal), Adebayo Awoniyi (Equal), Olajide A. Fagbolagun (Equal), Christian C. Makwe (Equal), Joseph A. Olamijulo (Equal), Ayodeji A. Oluwole (Equal), K.S. Okunade (Equal), O.K. Ogedengbe (Equal), O.F. Giwa-Osagie (Equal). Software: Sunday I. Omisakin (Equal), Aloy O. Ugwu (Equal), Olaniyi A. Kusamotu (Equal), Sunusi R. Garba (Equal), Adebayo Awoniyi (Equal), Olajide A. Fagbolagun (Equal), Christian C. Makwe (Equal), Joseph A. Olamijulo (Equal), Ayodeji A. Oluwole (Equal), K.S. Okunade (Equal), O.K. Ogedengbe (Equal), O.F. Giwa-Osagie (Equal). Validation: Sunday I. Omisakin (Equal), Aloy O. Ugwu (Equal), Olaniyi A. Kusamotu (Equal), Sunusi R. Garba (Equal), Adebayo Awoniyi (Equal), Olajide A. Fagbolagun (Equal), Christian C. Makwe (Equal), Joseph A. Olamijulo (Equal), Ayodeji A. Oluwole (Equal), K.S. Okunade (Equal), O.K. Ogedengbe (Equal), O.F. Giwa-Osagie (Equal). Visualization: Sunday I. Omisakin (Equal), Aloy O. Ugwu (Equal), Olaniyi A. Kusamotu (Equal), Sunusi R. Garba (Equal), Adebayo Awoniyi (Equal), Olajide A. Fagbolagun (Equal), Christian C. Makwe (Equal), Joseph A. Olamijulo (Equal), Ayodeji A. Oluwole (Equal), K.S. Okunade (Equal), O.K. Ogedengbe (Equal), O.F. Giwa-Osagie (Equal). Writing – original draft: Sunday I. Omisakin (Equal), Aloy O. Ugwu (Equal). Writing – review & editing: Sunday I. Omisakin (Equal), Olaniyi A. Kusamotu (Equal), Sunusi R. Garba (Equal), Adebayo Awoniyi (Equal), Olajide A. Fagbolagun (Equal), Christian C. Makwe (Equal), Joseph A. Olamijulo (Equal), Ayodeji A. Oluwole (Equal), K.S. Okunade (Equal), O.K. Ogedengbe (Equal), O.F. Giwa-Osagie (Equal). Project administration: Adebayo Awoniyi (Equal), Olajide A. Fagbolagun (Equal), Christian C. Makwe (Equal), Joseph A. Olamijulo (Equal), Ayodeji A. Oluwole (Equal), K.S. Okunade (Equal). Supervision: Christian C. Makwe (Equal), Joseph A. Olamijulo (Equal), Ayodeji A. Oluwole (Equal), K.S. Okunade (Equal), O.K. Ogedengbe (Equal), O.F. Giwa-Osagie (Equal).