Some historical background

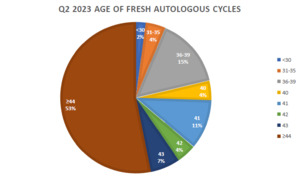

The Center for Human Reproduction (CHR) in New York City, likely, serves the most adversely selected patient population in the world, characterized by, among other phenotypical parameters, the oldest median age, above 43 for the last 5 years, and over 44 for the first time in 2023 (see figure).

This adverse self-selection by patients and, often, referring colleagues is based on an evolution in practice at the CHR over the last 15 years, after the center in the late 1990s made the decision, going forward, to make “the aging ovary” the centerpiece of its research and clinical practice. The decision was reached based on two basic observations: The first was that patient populations in fertility centers all over the world were getting older. An even more important motivation was, however, the recognition that, after ages 42-43, most fertility centers advanced patients rather automatically into third-party egg donation, a recommendation the CHR philosophically and ethically to this day opposes and which, unfortunately, at most IVF clinics still is current practice.

We, however, also recognized at the time that by concentrating our efforts on older patients and women who elsewhere often had been advised that their only chance at pregnancy was through egg donation, simply repeating the same kind of IVF cycles these patients in a large majority had failed elsewhere before, made absolutely no sense. We, therefore, saw our challenges to be similar to the original challenges IVF had faced during early IVF days in the 1980s, when pregnancy rates were still very low and live birth rates even lower.

There, indeed, existed another analogy in that time period because in these very early days of IVF practice, many IVF clinics did not accept women above age 38 into cycles because older women generally did not conceive at all. It was this analogy that especially motivated us because, even though women above age 38 by many clinics were refused treatments, some centers continued trying and, ultimately succeeded in finding ways to also achieve pregnancies and healthy deliveries in women above age 38. Had those centers not continued their attempts, we to these days might be sending patients into egg donation by age 38 rather than 42 to 43.

The research experience of this time period in IVF also taught us a second important lesson: When baseline pregnancy and live birth chances are very low, it does not take large prospectively randomized clinical trials to recognize when something works. This is why progress in IVF in early years was so rapid. But as one approaches rate-limited results, progress becomes more and more incremental, and when obtained outcome improvements are only marginal, though not less important, they become much more difficult to recognize, and, indeed, often require prospectively randomized trials. We, therefore, were confident that, even as a private, free-standing, mid-sized IVF center, with only academic affiliation, we through research would be successful in improving treatment options for our patients. We, moreover, also correctly predicted that such a process would feed upon itself, and that percentages of poor prognosis patients and the severity of their underlying conditions would increase proportionally to our success in treating our patients. And this is exactly what happened over the last 15 years, as our papers appeared in the literature and the word about the CHR’s specialization got out.

The breakthrough

In earlier years our progress happened only on the margins, mostly driven by more detailed diagnostic workups and more emphasis on details other IVF clinics often liked to ignore, - like, for example, immune problems. But this all changed around 2014, when we noticed that our improving pregnancy and live birth rates in older women gradually declined as one would expect with advancing female age until age 43, when the decline, suddenly, accelerated, This observation raised the question, what made this sudden acceleration happen? It was the answer to this question which not only became a principal breakthrough for the CHR, but in totality changed how our center managed IVF cycles in older women and younger women with premature ovarian aging (POA). As a consequence, an IVF cycle at the CHR in such patients is now, with exception of a small number of IVF clinics that have started to follow similar protocols, radically different from IVF cycles elsewhere.

HIER stands for Highly Individualized Egg Retrieval, a concept the CHR introduced into its practice starting in approximately 2014 after discovering through basic molecular research that follicles with advancing age luteinize at progressively earlier stages.1 Once follicles are luteinized, their eggs are over-mature and will not lead to pregnancy. The CHR, therefore, started to adjust lead follicle sizes at time of ovulation trigger according to patients age in order to remove oocytes from the follicular environment before they luteinized. In a first study, we set a lead follicle size of 16mm at trigger time for women at age 43.1 This stood in contrast to lead follicle trigger sizes between 18mm and 23mm which have been the routine for all IVF cycles since the inception of IVF and to this day are the customary trigger sizes at practically almost all IVF clinics.

Later we, however, learned that that a 16mm trigger size for many women was already too late.2 The CHR, therefore, has since been routinely retrieving many patients with lead follicle sizes as small as 11-12mm.2 The CHR’s two oldest women (and also the world’s oldest) to conceive with use of their own eggs, both only days from their 48th birthdays at time of embryo transfers, indeed, were triggered at lead follicle size 12mm.3

Though there was originally an assumption that so much earlier egg retrievals would increase the number of immature eggs, this did not happen. The spread of egg maturity, surprisingly, remained rather constant. This meant, however, that some eggs would, still be mildly immature (MI oocytes) or severely immature (GV oocytes). Because most of the CHR’s patients produce only small egg numbers, the CHR, in contrast to many other IVF clinics, since ca. 2014 has not been discarding MI and GV oocytes but, with quite good success, has been attempting so-called overnight rescue in vitro maturation (rIVM) on such oocytes.4 Only very recently, colleagues in Abu Dhabi, UAE, also confirmed the clinical value of this practice,5 which has been routine at the CHR since 2014.

Practicing rIVM for many years, the CHR’s embryologists and physicians more recently noticed in their weekly full-staff reviews of IVF cycles that the success of rIVM appeared to vary dependent on patient age. To explore this clinical impression further, they retroactively investigated their historical experience with rIVM in association with HIER in women of different ages. As now reported in a very recent publication in iScience, another quite groundbreaking discovery was made that changed how the CHR now views the physiology of MII, MI, and GV oocytes at different ages: The since establishment of IVF existing dogma that oocyte maturity grades are static, independent of female age, and maintain their functional ability of producing good quality embryos was proven wrong.6 As the study very surprisingly demonstrated, MII oocytes with advancing age significantly lost ability and GV oocytes significantly gained ability, while MI oocytes more-less maintained their ability to produce good quality embryos independent of age.

Conclusions and cautions

These obviously still preliminary results (which must be confirmed by further studies) were surprising and in several ways are potentially practice changing: (i) They reaffirm the validity of rIVM because all immature MI and GV oocyte in this study had undergone rIVM. (ii)The study also reaffirmed the importance of HIER because all patients in this study had undergone HIER cycles. (iii) This study, however, also suggested that egg retrievals may have to be triggered at even smaller lead follicle sizes than 11mm to 12mm as women get into ages beyond 45 years because most desired maturity targets at such ages may no longer be MII oocytes but Mi and GV oocytes. (iv) Finally, this study reaffirms that the routine disposal of immature oocytes reduces cumulative outcome opportunities for complete oocyte cohorts. Consequently, immature oocytes should routinely undergo rIVM.

The individualized timing of ovulation triggers to such very small follicle sizes and, therefore, at times extremely early egg retrieval, significantly shortens IVF cycles and mandates very close, daily observation of patients. That MII oocytes with advancing female age lose ability to produce good-quality embryos is, of course, also a potentially almost revolutionary finding because practically every IVF cycle in the world currently strives to maximize the percentage of MII oocytes in every IVF cycle’s egg-cohort. The final conclusion this recently published study, moreover, suggests is that, after over 40 years of clinical IVF utilization, the days of standard lead follicle triggers at 18-22mm are over, replaced by increasingly sophisticated individualization of IVF cycle timing based on age and other phenotypical parameters of patients, with the ultimate goal of precision medicine for every infertility patient.