Introduction

Preimplantation genetic testing-aneuploidy (PGT-A) is increasingly used in clinical screening to shorten the time to achieve a healthy newborn.

The existence of limitations with PGT-A, such as the invasive nature of the biopsy procedure and the need for technical ability, is leading to increased use of non-invasive preimplantation genetic testing for aneuploidies (niPGT-A) using spent medium (SMCs) by embryos analyzed, opening new horizons in genetic studies.

Although the clinical benefit of niPGT-A has not been shown,1–3 a retrospective cohort study has been necessary to determine the characteristics of patients undergoing genetic studies and first results obtained from the comparison of transferred euploid embryos versus elective transferred vitrified-thawed embryos that have not been analyzed for aneuploidy studies.

Materials and methods

This is a retrospective cohort study conducted from May 2022 to August 2023. To examine the relationship between morphology and euploid values, this analysis included day 5 and day 6 blastocysts that were vitrified at expansion stages 3 to 6 according to Gardner´s classification and transferred in single vitrified-warmed blastocyst transfer cycles. Blastocysts were divided into three groups based on their quality: top-quality AA, high-quality AB or BA, and poor-quality AC, CA, BC, CB, or CC.

Ovarian Stimulation and IVF Protocol

In all cases, ovarian stimulation was performed by daily injection of urinary or recombinant follicle-stimulating hormone with GnRH antagonist. The adjustment of daily doses was based in follicle size and serum E2 levels. A dose of 250µg/0.5ml of recombinant hCG was administered when the measurement of the dominant follicle was ˃ 17 mm. Oocyte retrieval was performed 36 hours later.

Oocytes were cultured for 4 - 5 hours in fertilization medium (Vitrolife) at 37ºC, 6.0% CO2, and 5.0% O2 before insemination by conventional in vitro fertilization (IVF) or intracytoplasmatic sperm injection (ICSI). Oocytes were examined 18-20 hours after insemination to determine the presence of 2 pronuclei. Fertilized oocytes were grown in 35µl of culture medium (G-TL™, Vitrolife) under OVOIL (Vitrolife) at 37ºC, 6.0% CO2 and 5.0% O2. Cultures were performed in Miri ESCO® and ASTEC AD-3100 incubators to the blastocyst stage (day 5, 6, or 7 post-insemination). In elective FET, laboratory workflow was performed according to standard clinical practices with non-isolation continuous culture from day 1 to day 6. Embryos for genetic analysis were cultured in G-TL™ medium (Vitrolife) on days 1-4 and the new G-TL™ medium for days 4 to 6 or 7. Spent culture medium (SMC) was collected on days 6-7, according to niPGT-A Igenomix protocol.

Vitrification and Warming

Blastocyst formed were vitrified and warmed following the manufacturer´s protocol (Cryotec® method). Dehydrated blastocysts were individually mounted in Cryotec. Vitrified blastocysts were cryopreserved in liquid nitrogen tanks until the day of embryo transfer (ET). Blastocysts were warmed at once before ET. Warming blastocysts were deposited in a hyaluronan-rich transfer medium (EmbryoGlue®, Vitrolife).

Embryo Transfer

All embryo transfers were performed under transabdominal ultrasound guidance by one doctor to avoid possible variability of results.

The endometrial preparation protocol was identical in niPGT-A and FET embryo transfer; the guideline was oral estradiol valerate 6 mg every 24 hours from day 0 until the start of vaginal progesterone 400 mg every 12 hours until week 12 if β -hCG was positive. In both cases, the Alertine regimen was the same, 10 mg every 24 hours orally starting on day 1 until detection of the heartbeat. Acetylsalicylic acid 81 mg daily and prenatal supplements are used in all cases from the beginning of the endometrial preparation.

Quantitative serum β-hCG analyses were performed on days 12 and 15 post-transfer. All patients ≥100 mIU/ml (day 12) and at least doubled on day 15 were considered positive b-hCG. Biochemical pregnancy rate was obtained by dividing the number of transferred blastocysts by the number of implanted. Clinical pregnancy rate (CP) was certified by ultrasonography at gestational weeks 3 to 4.

Spent cultured medium analysis

SCMs were analyzed using NGS-modified protocol with Ion ReproSeq™ PGS Kit technology (Thermo Fisher Scientific, USA). Library preparation and sequencing are done with the instruments IonChef™ and Ion S5system (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc, MA, USA). Sequencing results were analyzed using a validated algorithm developed by Igenomix.

Statistical analysis

The analysis was restricted to autologous cycles to compare outcomes with and without niPGT-A. Exclusion criteria included IVF cycles using donor oocytes and fresh IVF cycles. Furthermore, only cycles with embryo transfer and biochemical/clinical pregnancy outcomes were included.

Differences were analyzed using generalized estimating equations (GEE) logistic regression models. Covariates included in the model were women’s age, ART treatment, use of niPGT-A (clinical indication), day of transfer, embryo grade, embryo stage, observed aneuploidies, and sex of embryos analyzed.

A two-sided probability of p<0.05 was considered significant for all statistical tests. We conducted logistic regression to determine the association between euploid embryo transfer and elective FET.

Results

During the study period, 31 consecutive single vitrified-warmed day 5 and day 6 blastocyst transfers met the inclusion criteria. The average age of women included in the study was 37.4±4.2 for the niPGT-A group and 36.0±5.9 for FET group (p= 0.2953). Assisted reproduction techniques used were conventional IVF (64.0%) and ICSI (36.0%).

Reasons why couples decided to undergo niPGT-A were women’s age (46.7%), male factor (20.0%), RIF (16.7%), idiopathic infertility (10.0%), recurrent abortion (3.3%) and abnormal karyotype (3.3%). A total of 56 SCMs from 20 couples were collected. No paternal or maternal contamination was observed. The presence of the Y chromosome was detected in 21 SMCs (37.5%) versus the non-Y chromosome in 29 SMCs (51.8%); in six cases, non-informative results were reported (10.7%).

Many blastocysts obtained (n=56) were classified as high quality (n=33: 58.9%), followed by poor quality (n=13: 23.2%), and finally, top-quality blastocysts (n=10: 17.9%).

The most frequent aneuploidy found in the analyzed blastocysts was chromosome 16 involvement (17.5%), presenting as monosomies and trisomies in eleven cases. Frequent involvement of 2, 3, 15, 18, 20, and 22 chromosomes has also been observed (6.4% respectively). Aneuploidies in chromosomes 8, 11, 14 and X were observed in 4.8% of cases each, representing 19.2% of the total; chromosomes 6, 7, 10, 19, and 21 were observed in 3.2% of cases, chromosomes 1, 4, 5, 9, 13, and 17 in 1.6%. The presence of aneuploidies was not observed in the 12 and Y chromosomes.

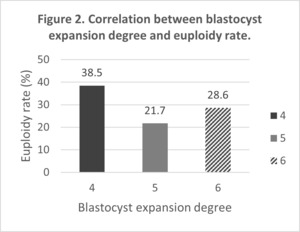

There was no correlation between euploid embryos and blastocyst quality (Figure 1). Neither was a correlation between the degree of blastocyst expansion and embryonic aneuploidies (Figure 2).

Establishing a comparison between genetically analyzed embryos and those transferred electively (niPGT-A vs FET) was possible due to the presence of similarities in morphological classification; 21.1% vs 25.0%, 46.2% vs 50.0% and 30.8% vs 25.0% in top, high and poor quality respectively.

Results of the comparison of biochemical pregnancy rate and clinical pregnancy rate in niPGT-A group versus elective FET are described in Table 1.

Discussion

Advanced maternal age and male factor were the main reasons for undergoing niPGT-A among the couples included in the study, reporting a positive awareness of the influence of both sexes on embryonic development. The quality given by embryologists based on blastocyst morphology is independent of the degree of euploidy of embryos analyzed. Monosomies and trisomies of 16 chromosomes have been often seen. These aneuploidies are incompatible with life and end in pregnancy loss during the first trimester. No correlation was observed between late blastulation and embryo quality with embryonic euploidy. Risks that must be considered include maternal DNA contamination and time-dependent DNA degradation. However, the possibility of maternal DNA contamination can be significantly diminished by meticulously washing the embryos in single-culture microdroplets and carefully removing cumulus cells.

No significant differences between niPGT-A and elective FET groups regarding biochemical and clinical pregnancy rates were observed. Comparable results were reported by Munné et al.4 and Yan et al.5 With considerable probability, the transferred elective blastocyst presented high aneuploidy rates due to late blastulation resulting in a reduction of clinical pregnancy rate.6

Conversely, the need for specific culturing conditions for niPGT-A embryos could reduce the implantation rate despite being euploid. This study proves that morphology assessment is as essential as euploid embryo status when seeing that euploid embryos with poor scores do not implant as optimal or high scores.

The study’s main strength is its thorough investigation of non-invasive preimplantation genetic testing for aneuploidies (niPGT-A), which uses culture media. The study’s sound methodology includes a retrospective cohort design, thorough patient data, and a comparison of pregnancy results with FET without niPGT-A. NiPGT-A is a promising alternative for determining the chromosomal status of an embryo, according to the study’s findings, with comparable biochemical and clinical pregnancy rates to FET without niPGT-A.

The impossibility of having a large number of participants in the study could limit the generalizability and extrapolation of the results obtained to the general population. In addition, this study has been carried out in a single center in the Dominican Republic, which limits the diversity of the participant pool. Hence, including populations from different geographical regions, socioeconomic statuses, races, or ethnicities becomes necessary.

A randomized control group in the study is necessary to avoid selection bias, which could undermine the reliability of the comparison between the niPGT-A and FET groups.

The current investigation’s study period might not be long enough to capture long-term outcomes that are crucial for determining the overall effectiveness of assisted reproductive technologies, such as pregnancy problems or newborn health.

Conclusion

Based on the results obtained, niPGT-A is a suitable alternative to replace the invasive procedures to assess the chromosomal status of embryos with safer and non-invasive techniques. To evaluate the chromosomal condition of embryos, we used niPGT-A. Our findings demonstrated that cfDNA from SCMs could be detected and amplified in 89.3% of cases revealing 66.1% of aneuploid embryos.

Comparing groups (niPGT-A versus FET), no significant differences were found in terms of implantation rate and clinical pregnancy rate.

In this study small number of samples is a limitation but we were, nevertheless able to properly characterize the genetic make-up of the particular blastocyst used in this study, which is the industry standard for determining the efficacy of this technology.

Despite these drawbacks, we can establish that niPGT-A, a minimally invasive technique, is accurate and trustworthy and can be used in addition to invasive PGT-A as a substitute. It will be possible to validate this incredibly promising technology and establish niPGT-A as a useful tool to help infertile couples have healthy offspring through large-scale randomized control experiments.

Acknowledgments

We acknowledge and appreciate the whole IVF staff for their support.

Conflict of interest

No conflicts of interest.

Authors’ Contribution

Conceptualization: Adriana Gosálbez Ferrándiz, Randolfo Medina Goliz, Víctor Montes de Oca, Juliana Martins Montes de Oca, Alicia Santos.

Data curation: Adriana Gosálbez Ferrándiz, Randolfo Medina Goliz, Juliana Martins Montes de Oca.

Formal Analysis: Adriana Gosálbez Ferrándiz

Funding acquisition: Víctor Montes de Oca, Juliana Martins Montes de Oca.

Investigation: Adriana Gosálbez Ferrándiz, Juliana Martins Montes de Oca.

Methodology: Adriana Gosálbez Ferrándiz, Randolfo Medina Goliz, Juliana Martins Montes de Oca.

Project administration: Adriana Gosálbez Ferrándiz, Randolfo Medina Goliz, Juliana Martins Montes de Oca.

Resources: Juliana Martins Montes de Oca.

Software: Adriana Gosálbez Ferrándiz.

Supervision: Randolfo Medina Goliz, Víctor Montes de Oca, Juliana Martins Montes de Oca.

Validation: Adriana Gosálbez Ferrándiz, Randolfo Medina Goliz, Victor Montes de Oca, Juliana Martins Montes de Oca, Alicia Santos.

Visualization: Adriana Gosálbez Ferrándiz.

Writing – original draft: Adriana Gosálbez Ferrándiz.

Writing – review & editing: Adriana Gosálbez Ferrándiz, Randolfo Medina Goliz, Víctor Montes de Oca, Juliana Martins Montes de Oca, Alicia Santos.

Corresponding author

Adriana Gosálbez Ferrándiz

Embryologist at Profert

Dominican Republic

E-mail: adriana.gosalbez@hotmail.com

__high_quality_(.png)

__high_quality_(.png)